When you work in emerging tech, you get asked for lists.

People want to know what the top 5 or 10 or 50 emerging technologies will be this year and beyond. So popular are lists of emerging technologies that the Biden White House published a 2024 update to the critical and emerging technologies list originally published by…you guessed it…the Biden Administration in 2022. The differences are subtle, but they speak volumes to industry, academia, and to government policy makers.

Lists of top emerging technologies are an exercise in futility (shhhhh…don’t tell McKinsey or Forbes). The pace of emerging technology development inherently means that any list must be updated or revised before it can be useful to industry executives or government policy makers. Further, lists of emerging technologies include finished products, which only captures part of the entire value chain. If the focus is on the end product, it is pulled away from the upstream technologies and materials required to manufacture those products.

In short, emerging technology lists lie to us.

The US Geological Survey produced a list of critical minerals first in 2018 then revised in 2022 including the 17 rare earth elements (REE) plus an additional 33 for a nice round 50. This list is currently driving initiatives like the Ukraine minerals deal and is a centerpiece of the tariff struggles with China. So, why do people want to see lists that include AI and quantum computing when critical minerals are driving so much of the emerging technology landscape today?

US policy makers have been touting sanctions that prevent adversaries from importing semiconductors or other consumer technologies and showcase the fates of Huawei and ZTE as evidence of efficacy. However, there’s another game afoot as outlined in Revenge of Raw Materials: the counter move by China to restrict US access to raw materials. The US should be not only be building lists of raw materials rather than of finished technologies, but it should also undertake a rigorous effort to:

Educate Americans across sectors on what these materials are used for and why they matter.

Change the psychology of how Americans think about rare earth element supply chains.

Study new economic models for rare earth element extraction and distribution that give the US an advantage.

Recognize the impact of global economic actions on its access to raw materials.

Before the US can achieve dominance in emerging technologies across their value chains, it must build a long-term strategy that prioritizes changing the strategic approach to REE extraction and processing. China spent over 15 years consolidating its REE industry and protecting its REE refining technology to control over 80% of global REE processing to pair with its 40% of proved reserves. The US is unlikely to be able to close the gap on access to the raw materials, but even that book is not closed yet. Creating such world redefining policy should start with an understanding of how we got here and where we stand today.

What follows is a discussion on the real numbers of REE proved reserves, their processing, and the respective actions the US and China have taken since 2010 to put us where we are today. For more information on specific industry impacts, read my piece on neodymium and check back here for the next in our series on specific raw materials.

Reserves

Raw material reserves have dominated the geopolitical consciousness for centuries. The materials change with the evolution of technology, but oil is the easy one. Oil’s application as a raw material in a multitude of products touches American life and life around the world every hour of every day. Events like the 1973 oil embargo and two wars in the Persian Gulf caused fluctuations in the market that people felt in their wallets. Foreign aid, wars, diplomacy, and all manner of state power levers have been pulled in pursuit of oil to the extent that Americans understand how important oil is and how important relationships with countries with proved reserves are.

Proved reserves tell us how much of a given raw material is inside a given country with a certain level of confidence. The CIA World Factbook defines proved reserves this way:

Proved reserves are those quantities of petroleum which, by analysis of geological and engineering data, can be estimated with a high degree of confidence to be commercially recoverable from a given date forward, from known reservoirs and under current economic conditions.

The CIA World Factbook maintains an estimate of the proved reserves of petroleum for 214 countries (numbers 99-214 are all zeros; that’s 115 countries with no proved oil reserves). The countries at the top of that list will surprise few:

Venezuela

Saudi Arabia

Canada

Iran

Iraq

Kuwait

UAE

Russia

Libya

Nigeria

The reason this list surprises few is because we’ve all been hearing about these countries relative to oil for decades on the news, and in some cases the US has fought wars in or in defense of some of these countries.

Here’s where lists matter.

A list of the countries with the top 10 proved reserves of petroleum carries a lot of information about the world. For decades, policy makers and strategists have been looking at this list and making globally consequential decisions that have impacted elections, toppled regimes, and made or broken fortunes.

The list they did not base those decisions on was one that included the finished products to which oil contributes.

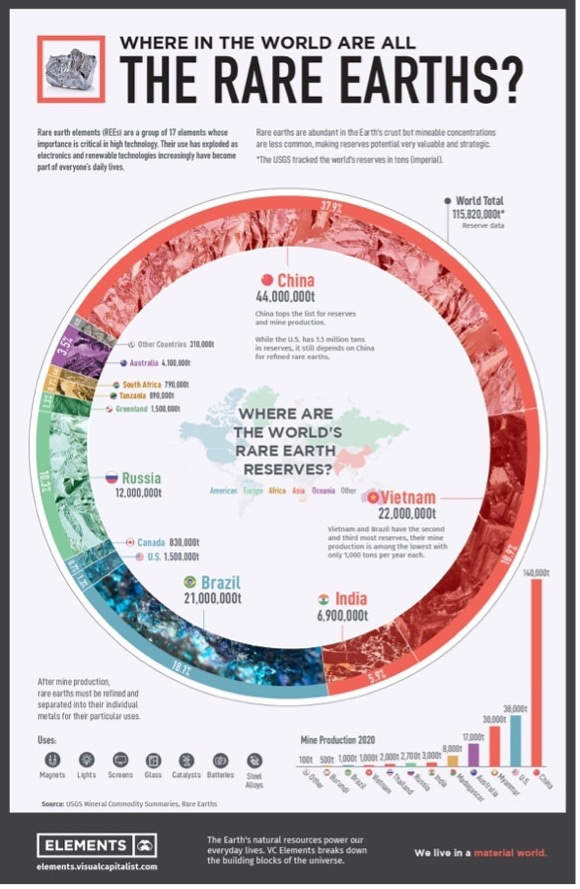

A less familiar but equally consequential list is that of countries with proved rare earth elements (REE) reserves. This list looks a lot different than the oil list, a list that has driven significant geostrategic activity for decades. The look and character of this list is what matters more in 2025 than any list of top finished emerging technologies:

China (40% of proved reserves)

Vietnam (19%)

Brazil (18%)

Russia (10%)

India (6%)

Australia (3%)

US (1.3%)

Greenland (1.3%)

Tanzania (.8%)

Canada (.7%)

*Numbers 8-10 had zero mining production in 2020

This list turns out to be very informative and should make even casual news observers sit up in their chairs. There are significant geopolitical activities and posturing that can be explained by this list. Many might notice Greenland and recall the Trump Administration’s calls for Greenland to become a US territory. Importantly not on that list is Ukraine, a country with which the Trump Administration announced a deal for REEs and critical minerals. According to news reporting, the deal includes;

Copper

Lithium

Titanium

Graphite

Beryllium

Uranium

Lead

Zinc

Silver

Nickel

Cobalt

Manganese

These are valuable minerals that appear on the USGS critical minerals list but are decidedly not the 17 minerals that constitute REEs. So poor is our collective understanding of REEs that the term is often used interchangeably with other elements, but just from these two lists, we should observe two important points:

1. Even if the US were able to get access to Greenland’s 1.3% of proven reserves and add Ukraine’s ~0%, that would still only get the US access to 2.6% of global proved reserves.

2. The delta between China’s 40% of proved reserves and the US’s 1.3% is telling, but even that tells only part of the story.

Being able to access REE deposits through mining is part of the battle, and the US does have an operational REE mine in San Bernardino County, but it is the only such mine in the US and most of its REEs have historically been exported to China for processing. Even if the Mountain Pass mine can produce at full capacity in the coming months and years, it will still suffer from a lack of domestic processing capability. As of April 2025, the Mountain Pass mine has stopped exporting its raw REEs to China citing tariff concerns and the lack of economic viability in continued exports under a 125% tariff.

More on proved reserves next week.

Processing

China not only sits on 40% of proved reserves of REEs, it also enjoy a staggering 80% share of global processing capabilities…and the value of those processing capabilities is not lost on them. China has been restricting the export of its refining and processing technology since at least 2010, but potentially back to 2008. China shut off export of technology to process neodymium two years ago, far before the tariffs and trade war began.

China produces about 210,000 metric tons of unprocessed REEs per year to American’s 43,000 metric tons. The devil is truly in the details because while there is a 167,000 metric ton delta, processing is where China has a nearly insurmountable lead. The US exports some of its unprocessed REEs to China where they are processed into usable form. This imbalance is part of what current US policy makers are trying to correct, but they are working against a 167,000 metric ton deficit with unworkable plans to make up the difference (see Greenland and Ukraine).

China has a significant technological and talent lead regarding REE extraction and processing. On April 23, 2025, China announced a major breakthrough in REE separation technology achieving 86% extraction rates and far surpassing western technologies. The ability to process heavy and light REEs is another place where China has a significant lead making the US task of replacing it more difficult.

While it is true that alternatives to China exist and that REEs are not rare in the sense of being difficult to find, we’ve seen this movie before. There have always been alternatives to the oil producing countries list, but at scale those alternatives become difficult to capitalize on. Further, the processing and refining capabilities in the alternative countries is likely to pale in comparison to China’s making this a more difficult problem. Another argument is that REEs are often used in small quantities in finished materials, which is true…currently. As materials sciences evolve, the requirements for REEs could rise making the scalability problem more difficult. The US currently has neither the ability to expand its access to raw REEs in a meaningful way nor the ability to process them domestically. While building these capabilities is a noble goal, near term access still matters and its current economic policies are moving away from access, not toward.

This is part one of a two part series on the current state of rare earth element mining. Stay tuned for part two next week!

Connect with us: Substack, LinkedIn, Bluesky, X, Website

To learn more about the AI products we offer, please visit our product page.

Nick Reese is the cofounder and COO of Frontier Foundry and an adjunct professor of emerging technology at NYU. He is a veteran and a former US government policymaker on cyber and technology issues. Visit his LinkedIn here.